By: Anjalee Udawatta & Lakshitha Edirisinghe

In Sri Lanka, conserving nature is a constitutionally established duty of both the State and citizens. As such, EIA becomes a tool with which to enforce constitutional provisions.

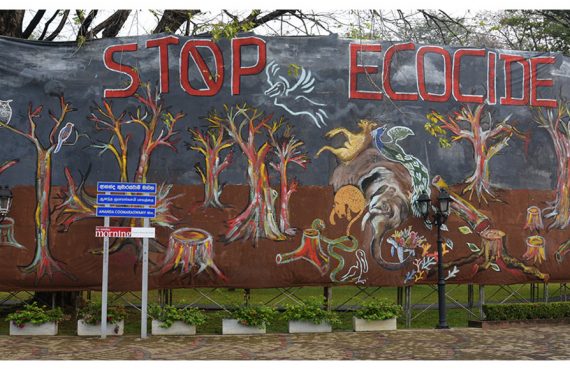

With the escalation of development activities and the influence of international agreements, environmental conservation has emerged as a major concern since the 1970s. Even in this day and age, it is becoming increasingly evident that environmental conservation is a dire need for the continuity of the entire human race. At the same time, the challenges to protect the environment are also mounting.

Protection of the Environment as a Right and Duty

In light of the crucial need to protect and preserve the environment, States such as Nepal have given a constitutional recognition to the right to live in a clean environment, according to Article 16 (1) of the 2007 Interim Constitution of Nepal. Neighboring India has recognized that the right to life is a fundamental right under Article 21 of the Constitution and it includes the right to enjoyment of pollution free water and air for the full enjoyment of life in leading cases such as Subhash Kumar v State of Bihar.

In Sri Lanka, the legislators have laid down provisions on management and protection of the environment in the 1978 Constitution. Although not included as a fundamental right, as per Article 27 (14) it is a directive principle of State policy to protect, preserve and improve the environment for the benefit of the community. According to Article 28 (f) of the Constitution every person of Sri Lanka also has a fundamental duty to protect nature and conserve its riches. Thus there is an obligation upon both the State and the people to protect the environment.

This then brings us to a question; how is the EIA process related to such rights and duties?

The EIA in Brief

Before perusing the question, it is essential to understand the basic idea implicit by EIA, which is ‘look before you leap.’ The EIA determines the amount of damages that a project will do to the environment before deciding whether and how to carry it forward. The ultimate objectives of conducting an EIA are to achieve sustainable development by searching for the most environmentally friendly alternatives, minimizing negative impacts, maximizing positive impacts and integrating environmental costs and benefits into the overall project analysis. According to the CEA, the purpose of EIA is to ensure sustainable investment for developers and a livable environment for the people. It is therefore evident that the EIA is a process specifically designed to preserve and protect the environment.

Environmental protection is directly connected to human rights, in countries such as Nepal and India. Even in a Sri Lankan context, conserving nature, as mentioned earlier, is a constitutionally established duty of both the State and citizens. As such, EIA becomes a tool with which to enforce constitutional provisions.

The State and the Public’s Duties Perspective of EIA in the Sri Lankan Context

The carrying out of an EIA was first introduced to Sri Lanka by the Coast Conservation Act, No. 57 of 1981 but was limited to a defined strip of coastal zone. Subsequently, National Environmental (Amendment) Act No. 56 of 1988 (NEA), introduced the EIA system to the entire island. In terms of the NEA, it is mandatory to conduct an EIA in respect of certain categories of prescribed activities recognised in the Gazette 722/22 of 24th June 1993 and 859/14 of 23rd February 1995. Additionally, the Fauna and Flora Protection Ordinance, No. 02 of 1937 as amended, North Western Province Environmental Statute, No. 12 of 1990 and National Heritage Wilderness Areas Act, No. 03 of 1988 also include provisions on EIA. Leading cases such as the Heather Mundy case and the Katunayake Expressway case have reinforced the importance of the EIA process and the vitality of it being carried out, prior to developmental activities.

The cumulative effect of this plethora of legislations and case laws ensures that the State is held accountable to fulfill its obligations towards the protection of the environment. Thus, even State sponsored development programmes are subject to the EIA process. The State also has an obligation to ensure that the proper EIA procedure is followed even in projects led by private entities. While on one hand it ensures rule of law, the positive impacts of a proper and effective EIA would ultimately be enjoyed by the overall citizenry.

One of the key features of the EIA procedure laid down in Sri Lanka is public participation, which is a significant form in which the people are able to fulfill their constitutional duty to protect and conserve nature’s riches. The public can participate in the ‘scoping’ stage, review the EIA within 30 days, request clarifications from the project proponent through the project approving agency (PAA) and may, at the discretion of the PAA, participate in a public hearing. Throughout the years, the public has actively engaged to review about 200 EIAs and in certain instances EIA has been implemented due to public pressure. For example, in 1999, despite the government having issued a gazette proclamation annulling EIA legislation for energy generation projects, the Minister of Power had to publicly proclaim that EIA would be conducted for a 300MW Coal Power Plant in Puttalam due to public protests.

The EIA process has not only become a mechanism for transparency and public review of projects, but has also facilitated a citizen’s fundamental duty to protect the environment, which can be carried out through active engagement in the EIA process. At this point it is quite pertinent to note the words of Justice Shiranee Thilakawardena in the Watte Gedera Wijebanda v Conservator General of Forests and Others case:

“Human kind of one generation holds the guardianship and conservation of the natural resources in trust for future generations, a sacred duty to be carried out with the highest level of accountability.”

List of References

- Amarasinghe and Others v The Attorney-General and Others [1993] 1 Sri LR 376

- Central Environmental Authority- Frequently Asked Questions about Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) (http://www.cea.lk/web/en/faq)

- Gazettes Extraordinary No. 772/22 of 24th June 1993 and No. 859/14 of 23rd February 1995 (https://efl.lk/relevant-laws-regulations-and-guidelines/#1622817309653-1c68f7df-42c5)

- Heather Therese Mundy v Central Environmental Authority SC Appeal 58/2003

- Hennayake S.K., Environmental Impact Assessment in Sri Lanka (2008) Economic Review: June / July 2008

- Interim Constitution of Nepal 2007

- King, Thomas F- Environmental impact assessment and the law (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780123739629004325)

- Kodituwakku D.C.- The Environmental Impact Assessment Process in Sri Lanka (http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.517.2352&rep=rep1&type=pdf)

- Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources – Environmental Management Framework, Ecosystems Management, And Conservation

- National Environmental (Amendment) Act, No. 56 of 1988

- Subhash Kumar v State of Bihar (1991) 1 SCC 598

- The Constitution of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka 1978 as amended

- USAID/ Sri Lanka Natural Resources & Environmental Policy Project, International Resource Group Ltd. – Environmental Impact Assessment: The Sri Lankan Experience (https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNACF382.pdf)

- Watte Gedera Wijebanda v Conservator General of Forests and Others S.C. Application No. 118/2004

- Zubair L.- Challenges For Environmental Impact Assessment In Sri Lanka (http://water.columbia.edu/files/2011/11/Zubair2001Challenges.pdf)

No comments yet.