By: Piyumi Wattuhewa

Passing legislations enabling the provisions of environmental conventions would pave the way for the better implementation of EIA procedures.

The amount of international conventions constituting provisions relating to the environment and environmental protection is vast, especially when one considers the subject specific conventions as well as the regional and bilateral agreements that state parties enter into. Environmental Impact Assessment is often given effect in such agreements, though often not expressly; but can frequently be found under the guises of promoting overall transparency, accountability as well as enhancing public participation in environmental decision-making processes.

An Overview of International Conventions Concerning the Environment

The United Nations Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm, Sweden in 1972 was the first ever major conference in the world which recognized that the states have an obligation to be held into account for the effects their actions have on the environment. It paved the way to the Stockholm Declaration which is the first document in international environmental law to recognize the right to a healthy environment. The Stockholm Declaration is also significant due to the fact that it advocates for the States’ ability to use natural resources for economic and social development and simultaneously highlighting the need for sustainability, enacting environmental legislations as well as environmental education and research. It also posits 109 recommendations for governments, intergovernmental agencies and NGOS for the mitigation of environment-related issues.

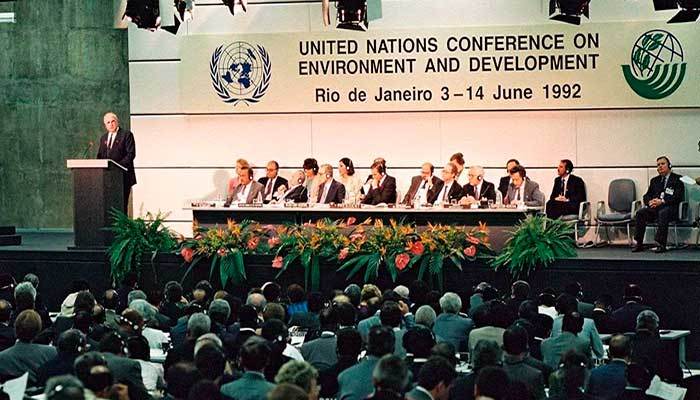

The United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) in 1992 in Rio de Janeiro, also known as the ‘Earth Summit’ can be widely considered as an extension of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment. From it, arose documents such as the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, Agenda 21, Forest Principles, Convention on Biological Diversity, Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification. The Rio Declaration is significant in itself as it expressly calls for the necessity for the states to have national environmental impact assessment frameworks in place through its 27 principles while also remaining a very ardent advocate for sustainable development.

Other International Agreements

In addition to the Declarations of Rio and Stockholm, there have been numerous other subject and area specific agreements which allude to the necessity of mechanisms to assess environmental impact in light of development as well as in the light of a State’s general obligations. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change which was also born out of the Earth Summit, recognizes the role of both developing and developed States alike in combating the adverse effects of climate change, calls for periodic assessments of States’ emissions of greenhouse gasses and calls for the adoption of national policies to mitigate their individual contributions to climate change. The Paris Agreement similarly advocates for States to contribute NDCs (Nationally Determined Contributions) as well as LT-LEDS (Long-Term Low greenhouse gas Emission Development Strategies) to combat/limit global warming. Notably, the Paris Agreement also obligates its parties to establish an enhanced transparency framework through which they would be able to transparently report on their climate change mitigation efforts.

- Espoo Convention

Convention on Environmental Impact Assessment in a Transboundary Context also called the ‘Espoo Convention’ is a United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) convention signed in 1991 and it is the first convention of its kind which set out the need to carry out Environmental Impact Assessments well early in the planning stages of development projects. The convention is limited in its application in two ways: first being that it calls for measures ‘to prevent, reduce and control significant adverse transboundary environmental impact from proposed activities’ (Article 2.1) which means that local projects which do not pose transboundary effects are largely exempt from being bound to the convention and secondly since the convention has long been ratified only by the member States of the UNECE and only been opened to ratification for non-members since the convention’s first amendment in 2014. Nevertheless, the Espoo Convention’s significance lies in its calls for the State parties to have environmental impact assessments as a minimum requirement for proposed projects (Article 2.7), its guidances to State parties in the preparation of EIA documentation (Article 4, Appendix II) and its acknowledgement of the need for post-project monitoring and evaluation along the lines of environmental impact. The convention also retains the importance given by the Stockholm and Rio Declarations in ensuring public participation in the environment assessment procedures as an affected party.

- Aarhus Convention

Going further in the area of enhancing public participation in environmental decision-making fora, the UNECE Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters, usually known as the ‘Aarhus Convention’ signed in 1998 was another landmark piece of legislation. It acknowledges the need for fostering public awareness, fostering access and dissemination of environmental information, enhancing public participation in environmental decision-making fora including EIAs as well as the right to judicial and administrative recourse in the face of a breach of environmental law.

How is Sri Lanka Faring?

Ideally, Sri Lanka should be in the forefront of the formation and the implementation of EIA processes: ours was one of the first countries in the South Asian region to legislate EIA procedures through the Coast Conservation and Coastal Resource Management Act, No. 57 of 1981 (as amended), the Fauna and Flora Protection Ordinance, No.2 of 1937 and through the National Environmental (Amendment) Act, No. 56 of 1988. Sri Lanka became a party to the Stockholm Declaration and the Rio Declaration in the very years they were introduced to the world, yet is not a party to the conventions of either Espoo or Aarhus. Due to the dualist nature of the country’s constitution, any international convention and/or agreement is not legally binding on the State even subsequent to ratification, unless and until the parliament enacts a domestic legislation which provides for their enactment. In terms of accountability and ensuring Sri Lanka’s compliance and support as a State in global environmental protection efforts, this is far from ideal. For an instance in which the parliament did pass legislation to give effect to the provisions of an international convention would be Marine Pollution Prevention Act, No. 59 of 1981. The large majority of international environmental legislation however, is yet to be incorporated into the domestic law.

Nevertheless it should be noted that despite the delays in the enactment of domestic legislations in line with international conventions, the Sri Lankan courts have been an ardent supporter and advocate for the implementation of conventional provisions in the cases which come before it and this was mostly noted in the case of Bulankulama and six others v. the Ministry of Industrial Development and seven others, also known as the Eppawala Phosphate Extraction case. The court made reference to both the Stockholm and Rio Declarations in pointing out the State’s obligation to strike a balance between its right to exploit the resources within its territory and achieving sustainable development.

Despite this precedent set by the courts, it remains as an undeniable fact that the courts are only limited to interpreting the legislation that has been enacted by parliament. Passing legislation by enabling the provisions of environmental conventions and providing them with adequate statutory footing would undoubtedly pave the way for the implementation of EIA procedures in a manner that would be in line with globally accepted international standards and reap the most benefits to all parties that are involved.

List of References

- Aarhus Convention – European Commission (https://ec.europa.eu/environment/aarhus/)

- Bulankulama and six others v. the Ministry of Industrial Development and seven others. SC (FR) Application No. 884/1999 (Supreme Court of Sri Lanka, April 7, 2000)

- Central Environmental Authority (http://www.cea.lk/)

- Constitutional Protection of Environment: The cherished Role of Our Judiciary (http://www.dailynews.lk/2021/02/18/features/241872/constitutional-protection-environment-cherished-role-our-judiciary.)

- Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-Making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters

- Convention on Environmental Impact Assessment

- Declaration of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment

- K. H. J. Wijayadasa, W . D. Ailapperuma – Survey of Environmental Legislation and Institutions in SACEP countries- Sri Lanka

- National Environmental (Amendment) Act, No. 56 of 1988

- Rio Declaration on Environment and Development

- Sri Lanka – Access information on Multilateral Environmental Agreements (https://www.informea.org/en/node/211/parties)

- Sri Lankan Navy – International conventions on environment to which Sri Lanka has become a party (https://www.navy.lk/navy-social-responsibility/conventions/treaties.html)

- The Paris Agreement

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe – Environment Assessment (unece.org/environment-policy/environmental-assessment)

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

No comments yet.